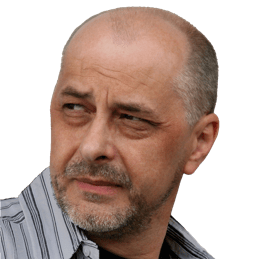

Vladimír Soukenka was born on 4 April 1953 in Prague. He studied stage design at the Secondary School of Applied Arts in the Prague district of Žižkov and architecture at the Academy of Applied Arts, Architecture, and Design in Prague, where he specialised in scenic design and studied in the studio of Professor Josef Svoboda. He got his first job in his field at the Workers’ Theatre in Gottwaldov (now the Municipal Theatre in Zlín) and worked there from 1979 to 1983. In 1983 Josef Svoboda hired him to work at Laterna Magika theatre, where he was a scenic designer and head of the technical arts department. In 1988 he began working as a studio architect for Czechoslovak Television Prague, creating set designs for television drama and fairy-tale productions and for recorded concerts and operas. In 1990 all the creative jobs at Czech Television were converted to free-lance work. In 1991 he was hired from a group of candidates to teach in the Faculty of Architecture at the Czech Technical University in Prague. He was hired by Professor Věkoslav Pardyl, whose footsteps he later followed in the study of the architecture of theatres and buildings for culture. He is the head of the Department of Interior and Exhibition Design (Ústav interiéru a výstavnictví), where he heads his own studio. In 2007 he and Pavel Bednář, a colleague, were helped to establish the Intermedia Institute (Institut intermedií), an interdisciplinary centre that unites the technical education of the Czech Technical University with the instruction in the arts offered by the Academy of Performing Arts (AMU).

Vladimír Soukenka was born on 4 April 1953 in Prague. He studied stage design at the Secondary School of Applied Arts in the Prague district of Žižkov and architecture at the Academy of Applied Arts, Architecture, and Design in Prague, where he specialised in scenic design and studied in the studio of Professor Josef Svoboda. He got his first job in his field at the Workers’ Theatre in Gottwaldov (now the Municipal Theatre in Zlín) and worked there from 1979 to 1983. In 1983 Josef Svoboda hired him to work at Laterna Magika theatre, where he was a scenic designer and head of the technical arts department. In 1988 he began working as a studio architect for Czechoslovak Television Prague, creating set designs for television drama and fairy-tale productions and for recorded concerts and operas. In 1990 all the creative jobs at Czech Television were converted to free-lance work. In 1991 he was hired from a group of candidates to teach in the Faculty of Architecture at the Czech Technical University in Prague. He was hired by Professor Věkoslav Pardyl, whose footsteps he later followed in the study of the architecture of theatres and buildings for culture. He is the head of the Department of Interior and Exhibition Design (Ústav interiéru a výstavnictví), where he heads his own studio. In 2007 he and Pavel Bednář, a colleague, were helped to establish the Intermedia Institute (Institut intermedií), an interdisciplinary centre that unites the technical education of the Czech Technical University with the instruction in the arts offered by the Academy of Performing Arts (AMU).

Vladimír Soukenka has created more than 80 scenic designs for the theatre and more than 50 sets for television studios and live broadcasts. He has worked on the stages of theatres in Brno, Ostrava, Olomouc, Uherské Hradiště, Prague, Ústí nad Labem and Pilsen. In the field of stage drama he has collaborated with directors such as Miloš Hynšt, František Laurin, Antonín Moskalyk, Lucie Bělohradská and Adam Rezek, in opera with Ladislav Štros, Václav Věžník and Tomáš Šimerda, in ballet with choreographers Zdeněk Prokeš, Jiří Kyselák, Jaroslav Slavický, Libor Vaculík, Ján Ďurovčík, and Petr Zuska, and with costume designers Josef Jelínek, Jana Preková, Irena Greifová and Milada Šerých. He has taken part in numerous exhibitions of scenic design in the Czech Republic and abroad and has won several awards for his work.